Edmond Halley was an English astronomer and mathematician. Halley’s Comet, one of the most frequently observed comets, is named after him. The son of a wealthy shopkeeper, Halley was born at Haggerston, near London, on November 8, 1656. He studied at Oxford. While still a student, he published treatises on astronomy that attracted the attention of the Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed. At Flamsteed’s suggestion, Halley left for the south Atlantic island of St. Helena, where he would study the stars of the southern hemisphere. The result of his studies was the Catalogus Stellarum Australium. In 1678 he entered the Royal Society, the British Academy of Sciences. He was 22.

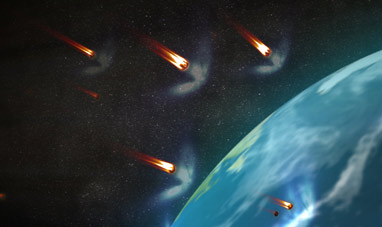

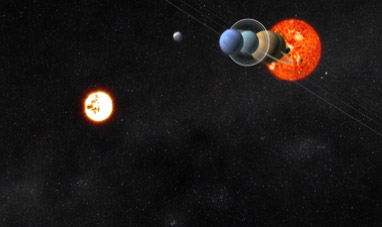

In 1684, Halley met Isaac Newton, who shared his studies on the force of gravity with him. Recognizing the importance of his research, Halley provided Newton with financial support and encouraged him to publish his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. In 1704, Halley became Professor of Geometry at Oxford. He became famous for his studies on comets, contained in the Synopsis Astronomiae Cometicae of 1705. Halley used Newton’s law of universal gravitation to calculate and describe the orbits of 24 comets. In particular, he reckoned that the comets seen in 1531, 1607 and 1682 were all one comet that passes near the earth roughly every 76 years. Halley predicted that the comet would pass by the earth again in 1758. The prediction proved to be correct. Unfortunately, Halley died 16 years before the comet returned, but Halley’s Comet would be named after him anyways in recognition of his accomplishment. Following the publication of the Synopsis, Halley began to study astronomical texts from antiquity. He noticed that some stars were in different positions than those described. He discovered that stars have their own movement and are not fixed in space, as had been long believed.

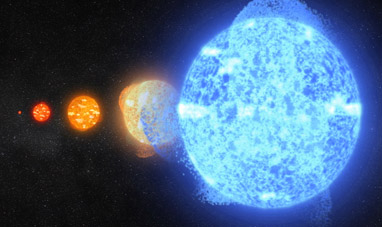

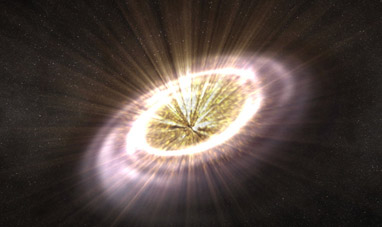

In 1716, he devised a method to measure the distance between the Earth and the sun. The method was based on the observation of Venus’s passage in front of the sun, and called for the co-ordination of observatories around the world. Due to the different angles, they would see Venus trace different trajectories along the outline of the sun. Measuring the distance between these trajectories and the distance between the observation points would show the distance between the sun and Earth. [For graphics: insert a graphic like this, to make clear the basic elements of the problem] The method was also put into practice after Halley’s death. It led to an estimate of the distance between Earth and sun only slightly higher than scientists’ current estimate: 149.6 million kilometers. In 1720, Halley was appointed Astronomer Royal. He continued his research at the Greenwich Observatory. Halley died there on January 14, 1742. He was 85.

In 1684, Halley met Isaac Newton, who shared his studies on the force of gravity with him. Recognizing the importance of his research, Halley provided Newton with financial support and encouraged him to publish his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. In 1704, Halley became Professor of Geometry at Oxford. He became famous for his studies on comets, contained in the Synopsis Astronomiae Cometicae of 1705. Halley used Newton’s law of universal gravitation to calculate and describe the orbits of 24 comets. In particular, he reckoned that the comets seen in 1531, 1607 and 1682 were all one comet that passes near the earth roughly every 76 years. Halley predicted that the comet would pass by the earth again in 1758. The prediction proved to be correct. Unfortunately, Halley died 16 years before the comet returned, but Halley’s Comet would be named after him anyways in recognition of his accomplishment. Following the publication of the Synopsis, Halley began to study astronomical texts from antiquity. He noticed that some stars were in different positions than those described. He discovered that stars have their own movement and are not fixed in space, as had been long believed.

In 1716, he devised a method to measure the distance between the Earth and the sun. The method was based on the observation of Venus’s passage in front of the sun, and called for the co-ordination of observatories around the world. Due to the different angles, they would see Venus trace different trajectories along the outline of the sun. Measuring the distance between these trajectories and the distance between the observation points would show the distance between the sun and Earth. [For graphics: insert a graphic like this, to make clear the basic elements of the problem] The method was also put into practice after Halley’s death. It led to an estimate of the distance between Earth and sun only slightly higher than scientists’ current estimate: 149.6 million kilometers. In 1720, Halley was appointed Astronomer Royal. He continued his research at the Greenwich Observatory. Halley died there on January 14, 1742. He was 85.