In March 1985, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced a series of sweeping reforms that changed the face of the Soviet Union, the federation of states that had governed Russia and most of Eastern Europe for nearly 70 years. Gorbachev’s new watchword was “perestroika,” the Russian work for restructuring. Ever since its inception in 1922, the Soviet Union’s political and economic model had been communism. Economic power lay in the hands of the state, which controlled industry, agriculture and all other natural resources. The state was governed by a single entity, the Soviet Communist Party. The party chose its own leadership internally. There were no elections. Commerce and trade outside the Soviet bloc was severely limited. In the long haul, however, the system proved unproductive. By the 1980s, the Soviet Union was mired in a deep economic crisis. Communist Party General Secretary Konstantin Chernenko, the union’s most powerful figure, died on March 10, 1985. He was replaced by Mikhail Gorbachev, who decided the time had come for the Soviet Union to make significant changes. Gorbachev overhauled the political system. Though the Communist Party maintained its supremacy, its members would be decided by direct popular vote. Gorbachev introduced the glasnost era, from a word that means “transparency” in Russian. [glasnost = transparency] Its hallmark was greater freedom for citizens and more openness toward foreign nations.

He signed a nuclear arms agreement after meeting with US President Ronald Reagan and ordered the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, where they had been mired since 1979 in an effort to impose a pro-Soviet regime. For the first time ever, trade between Soviet bloc nations and non-communist states was encouraged. The government also invited private involvement in the ownership and management of state companies. Soviet citizens were eventually issued vouchers that encouraged them to purchase stock in state companies. As shareholders, they could reap eventual dividends. But Russian citizens were poor. Most people chose not to become shareholders, underselling their vouchers for cash. As a result, the value of the state companies plummeted. Ironically, a voucher system designed to provide economic relief sent the Soviet economy into a definitive nosedive. Suddenly, Soviet citizens were poorer than ever. By 1990, peoples’ entire life savings had been wiped out. The economic fiasco provoked by perestroika was among the underlying elements that led to the Soviet Union’s definitive collapse.

He signed a nuclear arms agreement after meeting with US President Ronald Reagan and ordered the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, where they had been mired since 1979 in an effort to impose a pro-Soviet regime. For the first time ever, trade between Soviet bloc nations and non-communist states was encouraged. The government also invited private involvement in the ownership and management of state companies. Soviet citizens were eventually issued vouchers that encouraged them to purchase stock in state companies. As shareholders, they could reap eventual dividends. But Russian citizens were poor. Most people chose not to become shareholders, underselling their vouchers for cash. As a result, the value of the state companies plummeted. Ironically, a voucher system designed to provide economic relief sent the Soviet economy into a definitive nosedive. Suddenly, Soviet citizens were poorer than ever. By 1990, peoples’ entire life savings had been wiped out. The economic fiasco provoked by perestroika was among the underlying elements that led to the Soviet Union’s definitive collapse.

RELATED

SECOND ITALIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

THE FIRST CHINESE EMPEROR AND THE QIN DYNASTY

THE ARGENTINE DICTATORSHIP, 1976-1983

THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN

THE TROJAN WAR

THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR

NORMANDY LANDINGS

THE SINKING OF THE TITANIC

WESTERN SCHISM, THE

NATO (NORTH ATLANTIC TREATY ORGANIZATION)

THE FIRST INTIFADA

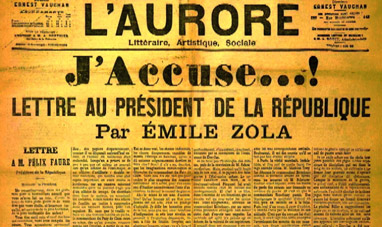

THE DREYFUS AFFAIR

THE TAIWAN ISSUE

THE SOVIET INVASION OF AFGHANISTAN

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

BUILDING THE SUEZ CANAL

MIKHAIL GORBACHEV

DISCOVERY OF AMERICA, THE

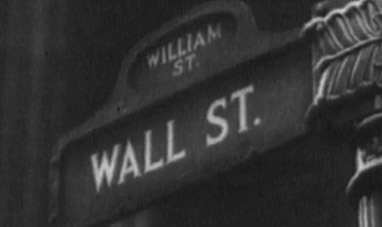

THE WALL STREET CRASH OF 1929

1968

THE FIRST MOON LANDING

THE 1973 CHILEAN COUP

THE KOSOVO WAR

THE MARCH ON TIANANMEN

TANGENTOPOLI

THE EXPEDITION OF THE THOUSAND

THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS

THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION

THE HUNGARIAN REVOLUTION OF 1956

THE EDICT OF MILAN

THE PRAGUE SPRING

THE ADVENT OF NAZISM

THE BIRTH OF ISRAEL

THE COLD WAR

THE BALKAN WARS OF THE 1990S

WORLD WAR I