Painter Umberto Boccioni was among the leading theorists and practitioners of Futurism, the first Italian avant-garde movement of the twentieth century.

He was born October 19, 1882 in Reggio Calabria. At the beginning of the 1900s Boccioni moved to Rome, where he frequented Giacomo Balla’s studio and grew close to the Italian “divisionist” movement that advocated putting colors directly on the canvas without mixing them first on a palette.

Disdainful of Italian culture, which he considered outmoded and provincial, Boccioni traveled widely before settling definitively in Milan in 1907.

Boccioni was fascinated by what he saw as a dynamic city at the height of industrial expansion. He painted Officine a Porta Romana and Mattino.

In La Città che sale he pulled away from “divisionism,” focusing instead on synthesizing light and movement. He abandoned perspective: turbines of vertiginous color spun and dove through his painting. This represented his shift into Futurism.

In 1910, along with Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, Giacomo Balla and Luigi Rùssolo, he signed on to a manifesto that abrogated ties to artistic tradition and promulgated the “aesthetic of speed,” intended to represent the progress and dynamism of modern times.

Boccioni was intrigued by the synchronic relationship between matter: He fused movement, memories and sounds. In Visione simultanee, buildings were piled one on top of another to invoke a parallel geometry.

In later paintings, reality was increasingly filtered through the painter’s mood and put onto the canvas transformed.

The human shape in the triptych of the “Stati d’animo,” for example, is little more than quick, oblique brushstrokes when in motion, and vertical ones when at rest.

In 1912, Boccioni participated in the first Futurist group show in Paris. These years were marked by frenetic activity as he sought to synthesize form and color.

The same year, he published “A technical manual for Futurist sculpture,” in which he applied Futurist experimentation to sculpture.

Even sculpted shapes showed differing kinds of dynamism: bulkiness created by movement; the persistence of images in the eye; the representation of space through the motion of a single body.

When World War One broke out, Boccioni headed for the front. He continued painting but abandoned the Futurist experiment, focusing instead on volume and monumentalism as they applied to the human form.

He died on August 16, 1916 following a bad fall from a horse. He was 33.

His artwork, all produced in less than a decade, represents a major Italian contribution to twentieth-century avant-garde art.

He was born October 19, 1882 in Reggio Calabria. At the beginning of the 1900s Boccioni moved to Rome, where he frequented Giacomo Balla’s studio and grew close to the Italian “divisionist” movement that advocated putting colors directly on the canvas without mixing them first on a palette.

Disdainful of Italian culture, which he considered outmoded and provincial, Boccioni traveled widely before settling definitively in Milan in 1907.

Boccioni was fascinated by what he saw as a dynamic city at the height of industrial expansion. He painted Officine a Porta Romana and Mattino.

In La Città che sale he pulled away from “divisionism,” focusing instead on synthesizing light and movement. He abandoned perspective: turbines of vertiginous color spun and dove through his painting. This represented his shift into Futurism.

In 1910, along with Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, Giacomo Balla and Luigi Rùssolo, he signed on to a manifesto that abrogated ties to artistic tradition and promulgated the “aesthetic of speed,” intended to represent the progress and dynamism of modern times.

Boccioni was intrigued by the synchronic relationship between matter: He fused movement, memories and sounds. In Visione simultanee, buildings were piled one on top of another to invoke a parallel geometry.

In later paintings, reality was increasingly filtered through the painter’s mood and put onto the canvas transformed.

The human shape in the triptych of the “Stati d’animo,” for example, is little more than quick, oblique brushstrokes when in motion, and vertical ones when at rest.

In 1912, Boccioni participated in the first Futurist group show in Paris. These years were marked by frenetic activity as he sought to synthesize form and color.

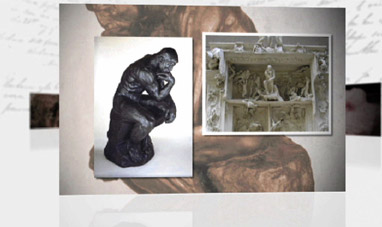

The same year, he published “A technical manual for Futurist sculpture,” in which he applied Futurist experimentation to sculpture.

Even sculpted shapes showed differing kinds of dynamism: bulkiness created by movement; the persistence of images in the eye; the representation of space through the motion of a single body.

When World War One broke out, Boccioni headed for the front. He continued painting but abandoned the Futurist experiment, focusing instead on volume and monumentalism as they applied to the human form.

He died on August 16, 1916 following a bad fall from a horse. He was 33.

His artwork, all produced in less than a decade, represents a major Italian contribution to twentieth-century avant-garde art.

RELATED

JOHN WAYNE

ANTONI GAUDÍ

FRITZ LANG

JOHN CONSTABLE

LEONARDO DA VINCI

EUGÈNE VIOLET-LE-DUC

MERCE CUNNINGHAM

GIANLORENZO BERNINI

SANDRO BOTTICELLI

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

EMILY DICKINSON

MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI

AUGUSTE RODIN

INGMAR BERGMAN

JEAN AUGUSTE DOMINIQUE INGRES

STANLEY KUBRICK

FILIPPO BRUNELLESCHI

WOODY ALLEN

RENZO PIANO

VITTORIO DE SICA

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

GIOACCHINO ROSSINI

TITIAN

CHARLES BUKOWSKI

JOHANNES BRAHMS

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF

SEAN CONNERY

FRANCIS BACON

MARTHA GRAHAM

JACQUES LOUIS DAVID

ANDREI TARKOVSKY

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT

MIES VAN DER ROHE

EURIPIDES

JOEL AND ETHAN COEN

BRAD PITT